Emulating Component Behavior with JavaScript Closures

by Dan Valinotti | Thursday, June 3, 2021 - 9 min readIntroduction

Recently, in an effort to level-up my advanced JavaScript knowledge, I've been diving into the "wonderful" world of Closures. If you've done any research on how Closures work in JavaScript for yourself, I'm sure you understand that it can be very confusing at first. For reference, here is the definition of a Closure from the MDN Docs:

A closure is the combination of a function bundled together (enclosed) with references to its surrounding state (the lexical environment). In other words, a closure gives you access to an outer function’s scope from an inner function. In JavaScript, closures are created every time a function is created, at function creation time.

Got it? Me neither.

I think an easier way of understanding Closures is to think of them as a way of manipulating the way variable scoping works in JavaScript to create the effect of private variables or functions. Take this code snippet for example:

Example

function makeCalculator(x) {

return function add(y) {

return x + y

}

}

const calculateFive = makeCalculator(5);

console.log(calculateFive(4))

// Prints "9"

console.log(calculateFive.add(4))

// TypeError - calculateFive.add is not a function

So we now have a function called makeCalculator that takes a base value x, and returns a function that takes another parameter y and adds it to x. Note that, while the function add(y) exists in the function block of makeCalculator(x), it is not accessible by any functions created with makeCalculator. Basically, we have a Calculator component generator that obfuscates its addition logic from everything else, but is still clear in what it does from an outside perspective.

So, this is cool and all, but how can we actually use Closures in a practical application?

After thinking about this unique behavior for a while (talking to my cat about it), I figured out that we can emulate the behavior of Components, similar to frontend JavaScript frameworks like React, using this function pattern! Allow me to walk you through my thought process.

Initializing a Component

The first thing we need to do is write a function that, similar to makeCalculator, contains some data or functions related to our component, and returns a subset of those. And the first thing that we do with any variable, Class object, or component is initialize it. So lets write a function that does just that:

const createComponent = function(props) {

const propsMap = new Map();

const render = (props) => {

// Some rendering logic

}

return {

init() {

// Some initialization stuff

}

}

}

// NewComponent is assigned the value returned by createComponent

const NewComponent = createComponent({ name: 'Dan' })

NewComponent.init()

NewComponent.render() // This will result in a TypeError!

Now I've created the function createComponent, which returns a set of functions (for now, just init()), and also includes some constants that are accessible only to the functions executed inside the scope of createComponent. Then, I define a new variable NewComponent that is assigned the return value of createComponent, which will be an object containing init(). After NewComponent is initialized, I can call the init() function from it, but I won't be able to directly access the values of propsMap and render.

So we got something going here, but it doesn't really do anything yet. What I want it to do is, on calling init(), to render a new HTML element as a child of some other element, which in this case will be a <div> with an ID of "app". I also want those props I'm passing to be used in some way in that render.

Creating a New DOM Element

Here's how I accomplished this task:

const createComponent = function(props) {

// Assign props value to propsMap so we can properly update them later

var propsMap = new Map(Object.entries(props));

const render = () => {

var name = propsMap.get('name') || ''

var app = document.getElementById("app");

var el = document.createElement("div");

// Assign an ID so I can reference it somewhere else

el.id = "new-component";

el.innerHTML = name;

// Attach the new element to the root "app" node

app.appendChild(el);

};

return {

init() {

render(props); // Called on `init`, but still not available to NewComponent

}

};

};

// Create two independent components

const ComponentOne = createComponent({ name: 'Dan' })

ComponentOne.init()

const ComponentTwo = createComponent({ name: 'John' })

ComponentOne.init()

Now I've fleshed out the render function to actually create a new element in the DOM, and gave it an ID value so that we can reference it later through the document object. I also created an additional Map object named propsMap so that we can mutate props freely later on.

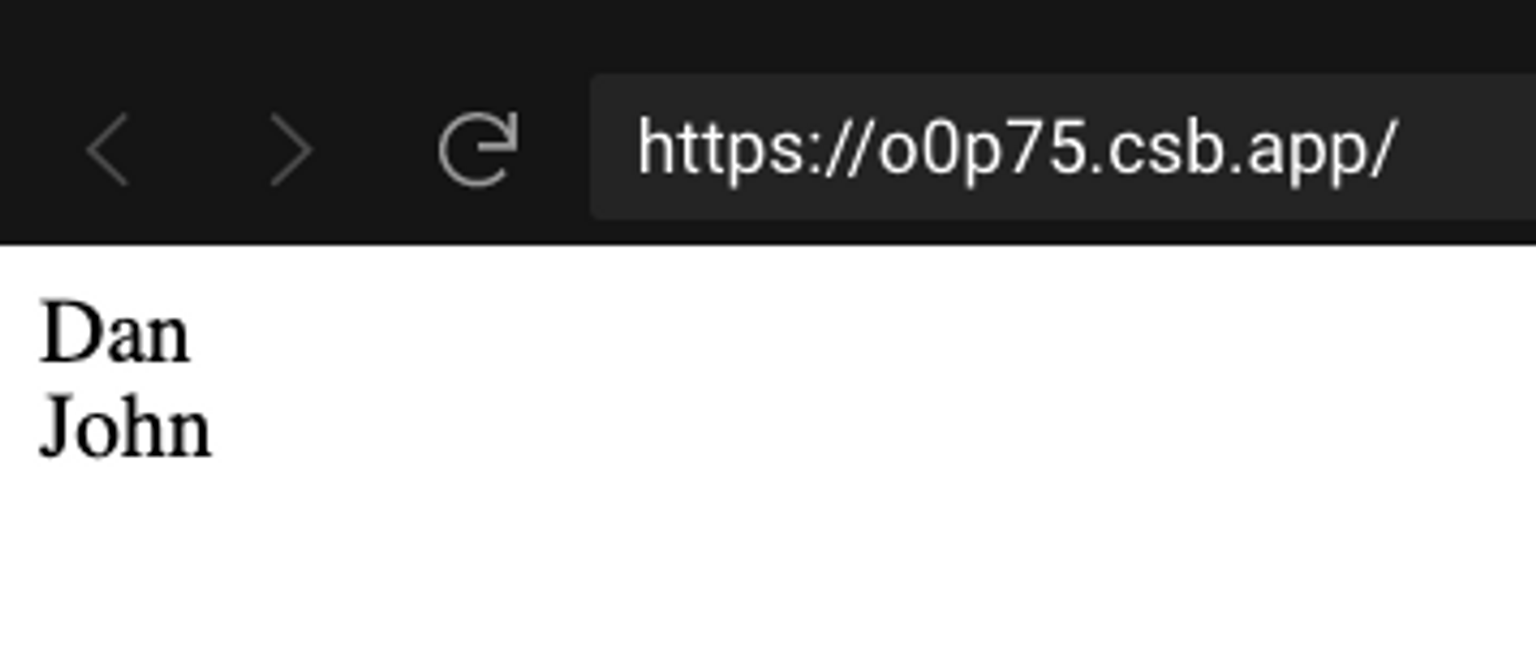

The meat of the render function is that it's getting the app element as a mounting point, creating a new <div> element with a unique ID, and set its innerHTML to the name string we pass in as props. Now, the result of running NewComponent.init() is shown below:

The result is that we have two independent components that render in the DOM, and are unaffected by each other. Absolutely bonkers!!! Nothing really crazy yet, but it's a start.

Make 'em Dynamic

The next step is to make our components dynamic, so that when we change the value of props the DOM element created by render will be updated accordingly. So we'll need another function available publically through ComponentOne or ComponentTwo so that we can update those props and trigger a re-render. We're also going to check the DOM before rendering to see if the component node already exists, to avoid duplicate nodes.

const createComponent = function (props) {

var propsMap = new Map();

// Allows us to mutate props freely

const setPropValues = (p) => {

const propEntries = Object.entries(p);

propEntries.forEach(([key, value]) => {

propsMap.set(key, value);

});

};

// Returns the current DOM node, or creates a new one and returns it.

const getRootNode = () => {

var id = propsMap.get("id"); // new prop for element IDs

// Check if the element exists in the DOM

const existing = document.getElementById(id);

if (!existing) {

// Append the root node to our app element

var app = document.getElementById("app");

var el = document.createElement("div");

el.id = id;

app.appendChild(el);

return el; // Return the new element...

}

return existing; // Otherwise, return the existing one.

};

const render = () => {

var name = propsMap.get("name") || "";

var el = getRootNode();

el.innerHTML = name;

};

// Update props to values from p and render in DOM

const renderWithProps = (p) => {

setPropValues(p);

render();

};

return {

init() {

renderWithProps(props); // props from creatComponent()

},

update(newProps) {

renderWithProps(newProps); // props from update()

}

};

};

So, there's a few things going on here now.

- There's a new function

setPropValues()that updates thepropsMapMap object with whatever values we provide it. - Another new function named

renderWithProps(), that assigns prop values usingsetPropValues()and renders the component to the DOM. - Yet another new function

getRootNode(), which checks the DOM to see if the component has already been rendered, and otherwise creates and attaches a new node to the DOM. Then it returns either the new or existing node. - I updated the

render()function to callgetRootNodeto avoid duplicate nodes being attached to the DOM when the component updates. - Last, I added the function

update(newProps)to the return value ofcreateComponent(), which takes a parameternewPropsand re-renders, making our component dynamic!

To test the encapsulation of props and behavior of rendering vs. updating these components, I added a couple of buttons to the DOM that call update({ ...newProps }) on click:

const ComponentOne = createComponent({

id: "component-one", // new prop

name: "Dan",

});

ComponentOne.init();

// (ComponentTwo init code here)

const btnOne = document.createElement("button");

btnOne.innerHTML = "Update One";

btnOne.addEventListener("click", function () {

ComponentOne.update({

name: "Peter"

});

});

// btnTwo code here that updates ComponentTwo

The Moment of Truth

Now, let's see if it actually works...

And it does! 🥳

How Closure Makes This Work

So, you might be thinking to yourself, "Sure, you've got some functions and some variables and functions within those functions, but I don't understand how closures fit into this." Allow me to explain.

The Closure here exists in createComponent and the functions contained and returned by it. We have variables and functions, like propsMap and renderWithProps(), which are used in the internal logic of our Component, but are not accessible by any variables that are assigned the resulting value of the expression createComponent(props). We specifically allow only certain functions, such as init() and update() to be called outside the function. This behavior keeps the internal workings of the Component hidden from its callers, but still provides all the necessary interfaces to create a dynamic component.

The code snippet below, similar to the first example, demonstrates this distinction between our "public" and "private" values:

const component = createComponent({

id: 'example',

name: 'Dan'

})

// Renders a new node in the DOM with the text "Dan"

component.init()

// Updates the props of our component and updates the existing DOM node

component.update({

name: 'Peter'

})

// Results in a TypeError - component.render is not a function!

component.render()

Our end result is essentially a super-watered down Virtual DOM API, but I think it serves as a good example for how a Closure can be implemented in JavaScript in a way that is both useful and clear in its implementation. I hope this tutorial has been helpful for you, whether you had no idea what a Closure was, or if you already knew about Closures but have never seen how it's used.

Here's a link to my code repo on GitHub.

If you'd like to mess around with this yourself, here is a link to the project on CodeSandbox.

Thanks for reading! 😊